#Drive 3, Mother Necessity

“With Mother Necessity and where would we be /Without the inventions of your progeny?” —Bob Dorough, Schoolhouse Rock!

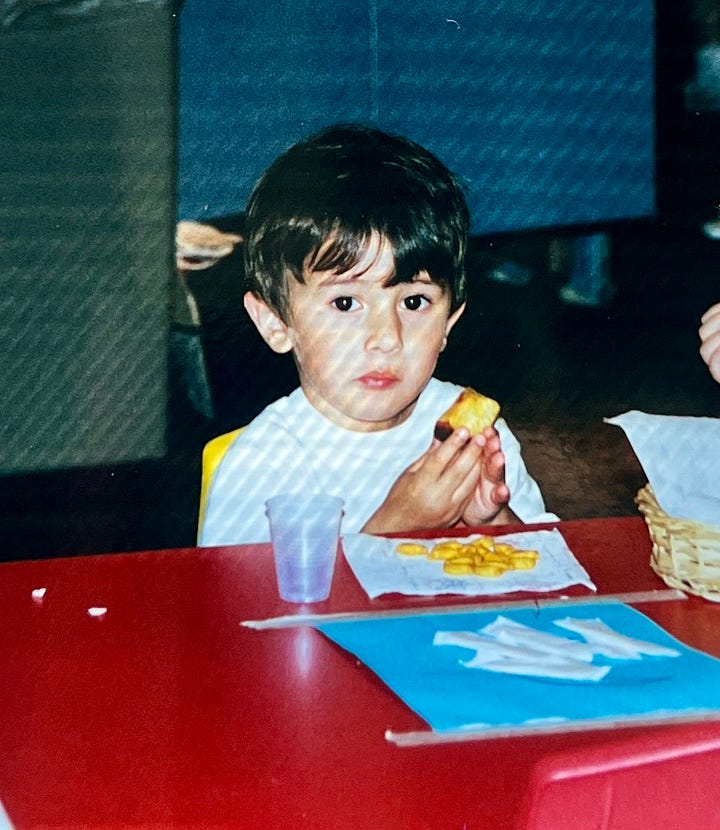

The fire in the hearth crackled. A spray of red hot embers popped to life in the air before disappearing into the darkness of the unlit room. Josh and Ally, almost five and a precocious two, giggled and chatted as they attempted to spread sleeping bags under a sleeper-sofa mattress that had been pulled out for the night.

Their lively interaction was at odds with the bleak circumstances and the dismal surroundings. Fortunately, most of it was hidden beyond the glow of the fireplace.

I’d spent many happy, rainy days building forts with blankets and sofa cushions with Wayne in that same room and listening to music with Dad as a child myself. It was surreal that on this day, the bedrooms didn’t have any furniture, just boxes, crammed mid-move as my parents moved into Granny and Bobby’s apartment.

Seven of the eight rooms of the fifty-year-old raised ranch, framed in rough hewn oak that was blissfully impervious to termites, had been gutted for renovation by their dad and I over the last two weeks. The great room on the ground level didn’t have walls or flooring, just exposed concrete block and slab, made colder by the late February night. Likewise, the kitchen had neither cabinets, appliances, or even a sink. Outlines of paint indicated where cabinets used to hang and holes in exterior walls implied “plumbing goes here.”

The hall bathroom upstairs had running water, so that’s where I rinsed our hot chocolate mugs and rubbed marshmallow residue off of the campfire sticks we’d used to make s’mores in the fireplace. Could be fun to roast hotdogs tomorrow night …

I pulled my T-shirt away from my collar bone and peered into the mirror. The angry streaks on my décolletage were fading. Small welts around broken skin were the only evidence of the altercation hours before. From his fingernails, I guess?

It wasn’t the first, nor would it be the last, violent episode in the span of a troubled marriage. I couldn’t stop replaying the scene as the fire died down—how he had advanced on me, pushing, shoving and yelling, multiple times, as I backed away from him, across the bedroom we had been painting until my back was against the corner.

Through arms crossed in front of my face and head, I had yelled, “Run next door! Get your grandmother, Josh! GO!”

When his attention had shifted and he started following Josh, I shoved him as hard as I could and ran past him.

Mom had crossed halfway across the 25 yards from the apartment, Ally in her arms, as I ran out of the house. “What’s going on?” she said, as I took Ally.

Before I could answer, he came through the door and screamed at Mom. “This has nothing to do with you, Mom,” he said. “It’s between me and Kim, Mom. ME AND KIM.”

Mom flushed bright red, but stood her ground and told him to stop yelling.

And he did. As per usual, the second I had a witness to his behavior, he backed off. His therapists assured me it was personal, “an interpersonal issue,” since he was “fine” at rehab, even “docile.”

This time, he gathered his tools, climbed in his work van—and drove away.

My elbows and knees trembled as the adrenaline receded from my veins, but my mind was clear. A gutted house was a more attractive option than going home with him. We didn’t have a bed, but we’d figure it out.

“You’re pregnant?” Mom had said, then laughed so hard she nearly tripped backwards down the three short steps from our kitchen to the deck.

It was August 1996 and I took a perverse pleasure in her little stumble, since she didn’t actually get hurt. My plan for starting a family had shifted into full gear three years ahead of schedule after only seven months of marriage—and she knew it.

She also knew that having children was something I had only recently agreed to. As a young adult, who struggled with the slow and painful death of her steel mill hometown. I argued that I didn’t want to add more lives to what I saw as a troubled world. Inside, I think I always wondered if a baby could survive having me as a mother.

Good thing I wasn’t too proud to put Mom on speed dial from the second I brought Josh home. He had his days and nights mixed up that first week. For those unacquainted with the phenomenon, this meant that he would barely open his eyes all day, and was then wide, wide, wide awake after nighttime feedings. Instead of slipping back to sleep, if only for an hour or more so a new mom could doze off, he would fuss and squirm.

Mom’s expert solution? “Walk him to sleep.”

She had run a childcare out of her home, specializing in infants and toddlers. And for 25 straight years, those babies kept coming. Her idea of “retirement” was taking care of newborn triplets 3 days a week.

Well, ok—walking seemed to do the trick the first two nights.

However, I was still sore from a natural birth and the many changes that interfere with sitting down and standing up after a first baby. Not to mention sitting and standing while holding said baby.

And at night, after Mom had gone home and his dad had gone to bed with, “Kim, I have to work,” my insecurities loomed large.

On the third night, I remember standing in the darkened kitchen in nearly the same spot where Mom had laughed with glee nine months earlier. My legs were heavy with fatigue, my upper body aching from rocking a 10-pound infant—and I was hitting a wall. What if I can’t get him to settle?

I wanted desperately to comfort the very unhappy Josh on my shoulder, but I couldn’t take another step. I couldn’t bounce him any more and I couldn’t sit down. I know I was crying nearly as hard as my newborn when his dad suddenly lifted Josh out of my arms and walked out of the room. I had yet to learn that I didn’t have to listen to my fears as a mom.

Falling into the closest chair, I dropped my head onto arms crossed on the table and may have dozed off.

Startled awake by Mom’s voice at the front door, I pushed myself up and went out to the living room. “Mom?” Warm tears spilled down my face the second I saw her. “ What are you doing here? It’s like … 3 am? ”

Ignoring me completely, he crossed in front of me, said, “Hello, Mom,” summarily put Josh in her arms, and returned to bed. She had to work the next day, too, but here she was, while my husband went back to sleep.

“It’s OK, Kim. Get some sleep,” Mom said as she bounced and soothed Josh. “He called me.”

Was it me, or did Josh quiet down the second she took him?

I assumed that my Baby Whisperer mother had comforted so many babies since starting her daycare that Josh just knew he was ok—Babies know.

“Mom, I think Josh likes you better than he likes me,” I said, more than once in those years. And I’m pretty sure I pouted or sulked. A petty, perfectionist hounds me from every tired or overwhelmed moment—and in those first few months, I had many.

“Kim, no one else can be his mom,” she said. “He might like lots of people, but being his mom makes you special.”

How many times did she comfort her daycare moms like that? The ones who cried as they dropped their kids off. The inexperienced moms, like me, who had to learn to recognize unspoken baby talk.

That drawing legs towards their belly showed pain, that squirming around in your arms meant wanting down. That a short, chirpy cry that irritated your ears communicated their irritation and, usually, a need for a nap. That the two-toned cry, the one that was louder at the end that could break your heart for them, meant they were hungry and basically were afraid they were dying, unaccustomed to having to wait for food.

It occurs to me lately, that being attuned to what a baby needs from first mew was something Mom was probably born with (unlike moi!). And that talent was amplified by having an asthmatic son whose every breath depended on her recognizing his unspoken signs.

What could be worse than watching your kids struggle, helpless to do anything?

Honestly, marriage to a man recovering from a coma and memory loss wasn’t great—and needs a whole other book to process. And once he was able to return to work, my focus was helping the kids, making up for what he couldn’t, or wouldn’t, do. (Yes, this is called “high functioning codependence.” I know that now.)

An early adopter of having a PC and dial-up modem at home, I had been dorking out over “You’ve got mail,” desktop publishing, and the World Wide Web for a several years when we separated. Information gives me a sense of control when life is utter chaos, the same way that fiction can whisk me away faster than a Calgon bath or a Peppermint Patty ever could.

The lifesaver information this time came from a free program called Confident Kids. Developed as a life skills program for Russian children whose parents were alcoholics, a local church offered it for kids in families going through divorce.

So this desperate mama learned along with her son that we’re not stuck, we always, always, always have choices—not to mention the myriad ways to name a feeling using the Alphabetical List of Feelings Words that came home with him.

I had a decent vocabulary, most readers do. But, using words to label feelings in life gives control? Who knew? I’d never seen that modeled in my life—real or fictional.

My feelings autopilot ran on something like determined or focused, usually on a schedule or task list and ranged from “escaping” to an impressionistic anger-fear mash-up that would crop up if I couldn’t get away. (Yes, Dorothy, this is classic avoidance.)

My first real clue that I’d been running away from troublesome feelings happened sometime in spring, 1994. I’d been enjoying a Meat Lover’s pizza and beer while watching Robin Williams and Dustin Hoffman in Hook.

At face value, this seems like a relatively blasé activity for a solo night after a busy week. However, when Wendy’s little daughter Maggie told Captain Hook, “You need a mother,” a tear slid down my face.

Surprised by my emotional reaction, I stopped to consider where it came from. I clearly still had a mother—But I’d lost Bobby.

And although that had been 18 years prior, I ugly-cried that night until I could barely breathe.

The emotions of my pizza night, on top of a failed attempt at being an alcoholic, prompted me to explore themes like grief, just enough to know I was terrible at it. I happened to excel at codependence and attachment issues. So, I got some counseling and read books like Love is a Choice, Boundaries, and Safe People.

Learning emotional intelligence at Confident Kids in the middle of a family crisis, taught by friendly, real-life husband-wife team was next-level. I devoured the take-home assignments for preschoolers and asked lots of questions. And if they ever looked at me with any judgement for the mess I was living, I never caught them.

I concluded that people who write for and teach kids are masters at distilling life into meaningful moments. Today, I’ll often start in the children’s library or websites with new research projects. They’re practical and informative on a level that doesn’t add to overwhelm (plus, cool pictures!).

So deep was my gratitude for Confident Kids that I volunteered for a vacation Bible school at the same church, summer 2000. 600+ kids were hosted at the weeklong event, plus 125 “Teacher Tots,” children of the volunteers. I assisted at the Teacher Tot arts and crafts table and was otherwise the fly on the wall.

If Aunt Sandy’s baby whispering impressed me, these women and men dazzled my inner toddler who was always ready to come out and play. Meanwhile, my inner nerd, with its penchant for Ticonderoga pencils, office supply stores, and happy little file drawers was downright warm and fuzzy by the efficient bliss.

Moving small groups of tots by having them hold onto a guide rope? Sing and play to hold attention? It was nothing short of brilliant. You’d never catch me jumping into a room full of toddlers in Mom’s daycare, but at this scale, I was proud to play a very small part.

Over the next year, I volunteered for weekday programs supporting 250 kids. Although I was rarely an in-classroom instructor, an all new realm of object lessons, child development conferences, and activity stations opened up to me.

Sure, I’d been in the elementary plays, decorated for proms, and painted plenty of banners for the proms and fundraisers. But this was practical world-building. It was orienting and reorienting one’s mindset and surroundings on purpose, to improve lives.

And I loved it—especially when I could bring the lessons home, on the occasions we three needed something like a couch-bed fort or s’mores in the fireplace.

Imagine my surprise then, when my therapist Judy responded to news of my separation from their dad with, “Don’t let them lose their mother, too.”

I was flummoxed (great word, that, and not enough occasions to use it). She knew my kids attended the programs I coordinated.

Today, I’d say she probably meant something like, “Stay emotionally connected to your kids,” or “Make sure you don’t check out” when Kim, the wife, is struggling with the separation.

But her words struck me more literally, as I got closer to time to register Josh for Kindergarten.

I am so glad you are writing your story, Kim.